Electronic laboratory notebook, labbook, logbook… whatever you want to call it, there are many different packages available for keeping track of your work in the lab. Why is Academic Labbook Plugin (ALP for short) different? This post attempts to present the current state of affairs in the world of academic labbook software, and to compare the main features and differences between them.

A word of caution: you are reading this post on the website for one of these labbook solutions. I am biased! Please make your own mind up, using what I write here as a brief guide.

Labbook software in the wild

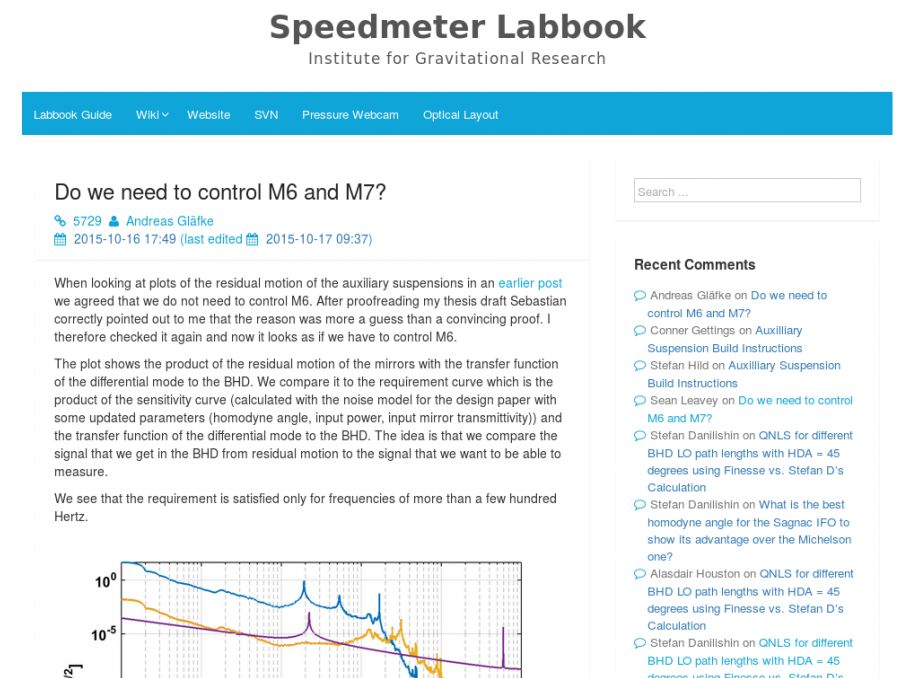

In my PhD at the Institute for Gravitational Research in Glasgow, UK, my first exposure to electronic labbooks was with a web script that rendered text files placed on an SVN repository on an internal university website. While it only allowed for placing a title and writing some standard text, it did use the powerful SVN version control system to track changes to posts over time, letting you revert back in time if you made a mistake. It also let you upload images and other data to the same directory and have this available to download through the browser. It was basic, but quite useful given the purpose it was to serve.

After a while we grew annoyed of this system, in particular its lack of ability to edit text through the browser that you view it with, the complete lack of any search abilities, and the inability to write rich content like lists, images, tables, etc. in-line with the text. We eventually moved to OSLogbook, or “Open source logbook”, provided by the Virgo Collaboration. This was a big step forward, with rich text capabilities and a generally nicer interface, but we were still not fully happy. I eventually bit the bullet and fired up a WordPress installation and hacked around with it. One of the huge advantages of WordPress is that it has a giant ecosystem of plugins that modify its behaviour in various ways. I hunted for some plugins to add the behaviours I needed – ability to specify multiple authors for posts, render mathematical equations in posts, send email updates, that sort of thing. I was able to find some that did more or less everything I wanted, and after a few hours importing the old data I had a shiny new labbook ready for my group to start using.

This loose collection of plugins has now grown into Academic Labbook Plugin, or ALP for short. I think it’s awesome, and I hope others find it useful too. But, before going further, it’s worth understanding what else is out there. ALP benefited from my experience using a few other labbook systems, and I want to go through each of them and highlight what is good and bad.

A note of caution

This is entirely my personal opinion, and I am obviously biased because I have developed one of the competing tools. I’ve tried to be honest about the strengths and shortcomings of each tool, but this post is basically a big advertisement for ALP (skip to the bottom to find out more about it). To get a more complete picture, it’s best that you test drive each of the options before making the final decision for your group.

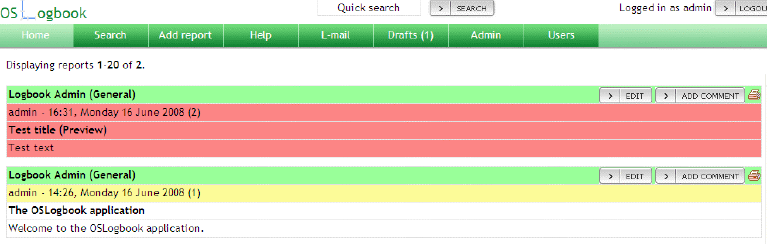

OSLogbook

OSLogbook was written in the spare time of a researcher in the Virgo Collaboration, building a gravitational wave detector in Italy.

It allows you to set “tasks” into which you could write posts, and there is a basic search capability to find text mentioned in posts. You can upload images, but only as attachments to posts – not inline with the content. The look and feel is pretty basic, and isn’t optimised for mobiles or tablets.

OSLogbook is still actively used, despite having very infrequent updates. It is used for documenting lab work at every gravitational wave detector except for GEO-600, and these labbooks are all publicly available:

It seems a few custom modifications have been made to OSLogbook on these sites. One of the changes made to the LIGO ones (and possibly the others, though I can’t check) are the addition of TinyMCE, which gives rich text editing support.

The good

- Image attachments (but not inline images).

- Categories.

- Limited rich text capabilities: bold, italic, lists, colours, etc.

- Basic search.

- Rudimentary login system.

- Somewhat clunky, but usable, comment system.

The bad

- No public updates in 10 years.

- No inline images.

- Lacks advanced rich text capabilities: widgets, blocks, mathematical rendering.

- Single permission structure: everyone can edit everything.

- Posts only attributed to one person.

- No tracking of revisions to content, and no ability to revert to previous versions of posts.

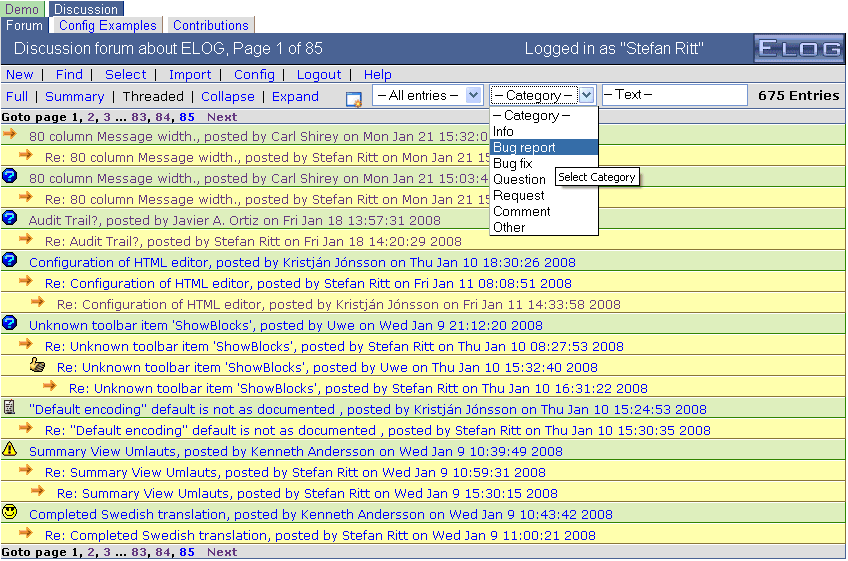

An old one: ELOG

The Paul Scherrer Institute developed ELOG as a basic labbook that keeps its data in flat text files, making it very easy to back up. It is reputedly used for many Large Hadron Collider experiments, and a few dozen other groups around the world.

It’s written in C++, making it super fast, but that also means it’s difficult for the average scientist to open up and modify to their liking. I guess if you’re after something basic and bulletproof, this is a good shout.

The good

- Easy to back up and restore data: old post revisions are stored if the system is configured to back itself up, and old versions are relatively easy to restore, but only for those with root access.

- LDAP / external group management support for allowing single sign-on access.

- Single user permissions: everyone can edit everything, but posts only attributed to one person.

- Relatively easy to revert to older versions of posts by using the backup system.

- Can render mathematics, but only as images (not sure if these can be edited later).

The bad

- Slow search when the archive of posts grows large (apparently).

- Uses old/weird technologies: it’s written in C++, which is almost unheard of for modern web applications – it might be more difficult than it really should be to extend the software with custom features should you be inclined to do so (that said, C++ makes it blazing fast at what it does). It also relies on old HTML syntax which will not work well on mobiles or tablets.

- Flat post category structure: no subcategories, tags, etc.

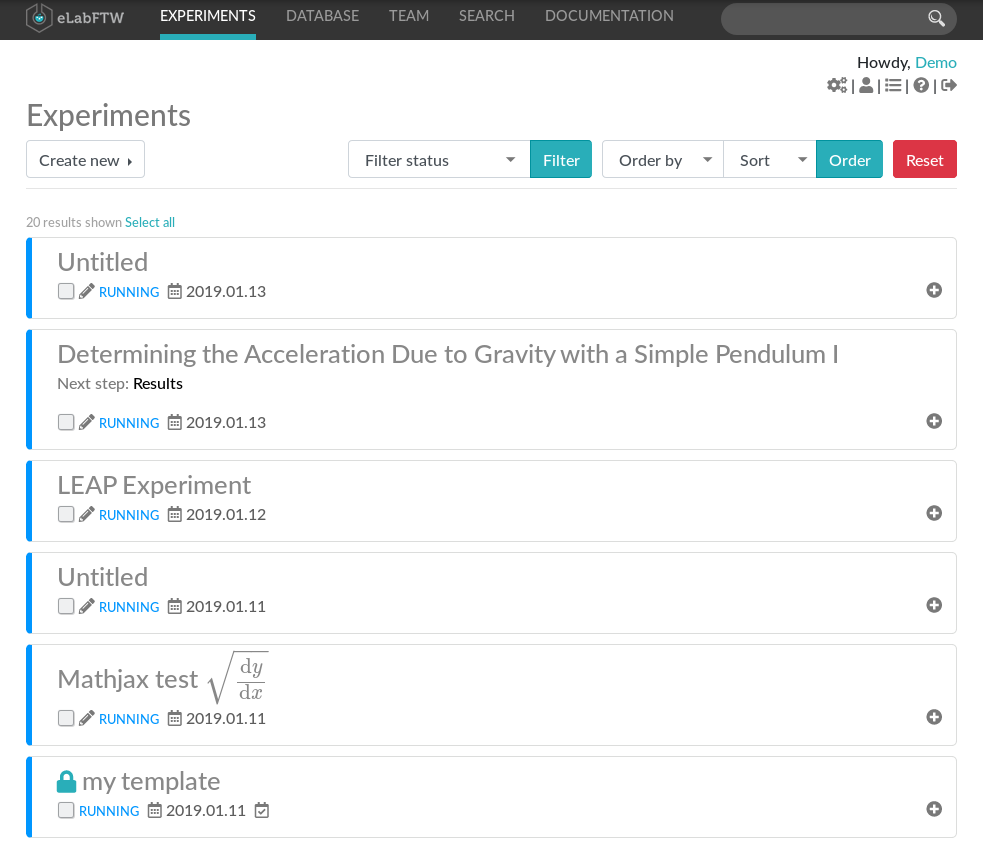

eLabFTW

eLabFTW is an open-source labbook, and similarly to ALP it was developed within academia, in this case by an engineer supported by Institut Curie, Paris.

From its screenshots you can see that eLabFTW is somewhat experiment-based, with each post representing a notebook where information should be place from start through to completion. When an experiment is created, it can be given an “In Progress” tag, and upon completion or failure it can be labelled as such. Posts are made within “databases”, akin to categories or experiment themes. They can only be contained in one database at a time. I am sure this particular workflow is useful for many groups, particularly life sciences where one must apply similar methods to many different groups of chemicals and rigorously note the results. In the groups I work with, though, this style is not as efficient as a chronological blog style, where posts represent little chunks of progress as part of a large, multi-year or multi-decade experiment. That said, the look and feel of eLabFTW is very nice, with JavaScript used to add interactivity, a nicely laid out panel of tabs, and intuitive interface. You can try out a demo here.

The good

- Revision history showing previous versions of pages, though apparently not with page diffs.

- Each user can set up their own “experiment templates” to provide pre-filled rich text on new posts. In ALP, this is strictly only possible as a global setting applied to all users, though users can save preconfigured blocks with pre-filled text that they can add to new posts.

- Mathematical rendering via MathJax.

- Parametric search.

- “Draw something” and molecule drawer widgets let users draw pictures and diagrams to support their posts.

- Access via an API, allowing you to integrate it with other services with a bit of programming.

The bad

- The organisation of posts might be a bit messy if you are used to a labbook showing sequential, chronologically ordered posts, though this is somewhat down to personal taste and can probably be configured in eLabFTW.

- Posts have no assigned author, meaning that you can’t search for posts made by a particular person. This seems a bit strange when coupled with the revision tracking feature – so you can tell what has changed but not who changed it, apparently.

- Posts can only be filed into a single “database”, meaning posts that cover different topics may be missed when searching through posts in a particular database.

Labfolder

This seems to be the most successful proprietary option for scientific labbooks. It’s got a flashy look and feel, using modern technologies that work on smaller and larger screens. The workflow is centred around single pages that have a skeuomorphic box-grid background, reminding you of your old paper labbook.

Where I work, at the AEI, we can access the “pro” version of Labfolder via the Max Planck Society. This gives you more storage space, more than 3 users, and the ability to export your data as simplified web pages. I’ve played around with it and it seems the pro version is the only way to really get a decent set of collaborative features, especially for organisations with single sign-on user accounts, IT departments, and group hierarchies.

A big part of Labfolder posts is the ability to add “data elements”, which are essentially key-value items associated with the text, which you can later search through, kind of like hashtags. This is a nice feature in principle, and probably offers good value to certain groups, but I see two problems with it: the first is getting people to actually use it, which, in the groups I’ve worked in, will require a lot of pestering. I know from experience that most people just want to write into an electronic labbook the same way they would write into a paper labbook (the tried and tested “aim”, “method”, “results”, “conclusion” style). The second problem is that simple key-value relationships are usually not enough to adequately describe blue skies research. There are usually caveats to any numbers you write into your labbook, like say “I annealed at 500° for only 10 minutes, not the usual 30 mins”. This requires putting a note into the text, where you may as well also mention the numbers.

There are other features that will no doubt be useful to some groups, like a materials database module. This is again essentially a wrapper around a simple key-value database, but might offer value to some groups. A more comprehensive feature list is available.

The good

- Uses modern web technologies, so works nicely on mobiles, tablets, etc., and the page is interactive – blocks are draggable, buttons can be clicked without the page reloading, etc.

- Experiment based posts, kind of like a single page of your paper labbook.

- Some sort of weird digital signature support. Maybe your institute requires some kind of boss signature for measurements (my work doesn’t), and this supports it… whatever it is.

- Likely to improve in the future as it is under active development by a well funded startup.

The bad

- Proprietary. No matter how many promises a private company makes about giving you access to their services forever, you should not rely on this. Ever. You can export pages as structured XHTML with the pro version, but it will take some work to port into a new system if you decide to ditch it after using it for a while.

- Seems to be targeted towards life science research, with discrete experiment pages rather than a list of chronologically ordered updates.

- Strict ownership of content as a conscious design choice: Labfolder seems to make a big deal out of making sure content is only editable by its creator (singular – no multiple author support), and encourages users who wish to expand posts to duplicate it instead of editing the original. The manual refers to “protection of intellectual property and compliance” as justification. I suppose this feature is useful in some fields where there might be bigger problems with plagiarism than in mine, but I find this feature rather frustrating.

- Related: can’t delete entries, even before they’re published.

- Not so advanced editor: can’t paste images from the clip board, can’t add files larger than 20 MB, no autosaving.

Note: it should be said that with Labfolder’s funding, they will probably be able to add support for some of the missing features above in the future if the users make a big deal about it. This is not necessarily true of the others, which are mostly hobby-scale operations.

Aside: custom Lotus Notes application

Post list display – showing in this case posts sorted by diary date.

Post view – edit like you’re writing a Word document, and display like you’ve saved it to a PDF.

In the previous section I alluded to GEO-600 not using OSLogbook, even though all the other gravitational wave detectors do. This is because GEO uses its own custom system, predating those of the other sites, based on a Lotus Notes application. Lotus Notes, for those who haven’t used it, is a general purpose package for word processing, emails, contacts, calendars, etc., hosted on institutional servers with user management capabilities. It was very popular in the 90s. One of its killer features at the time was the ability to build custom applications on top of the system, taking advantage of the full-blown, networked word processing package, inline images, syncing, user permissions, etc. Someone at the AEI, who host the GEO-600 project, did just that.

This is not available to the public, and Lotus Notes comes with hefty licence fees, but there are a few concepts that this labbook design does well and not well, so it’s worth discussing them.

The good

- Coauthor support: specify multiple authors for individual posts.

- Comments are full-blown posts shown indented and underneath the parent post. That means the commenter can use the full rich text editor, upload their own images, etc.

The bad

- Single permission structure: everyone can edit everything.

- No tracking of revisions to content, and no ability to revert to previous versions of posts.

Academic Labbook Plugin for WordPress

Take all of this with a heavy pinch of salt, because I wrote it. But I do think it covers a lot of the bases that the others do well, and because it’s built on top of WordPress you get the nice editor, media and customisation support.

The good

- Backed by the open-source WordPress platform, which runs 30% of the web. The platform is incredibly customisable, and ALP can run alongside other plugins to tailor the site more closely to your needs. That means…

- Access to the giant WordPress plugin ecosystem. Not all plugins are well written, but there are a few great ones out there that add extra capabilities to WordPress, and can be used alongside ALP.

- A powerful API, allowing you to integrate the labbook with other services. For example, it would be possible to have a particle counter in your lab post a message to your labbook to warn people when it gets too dirty.

- Full coauthor support, with multiple permission levels: posts can be “coauthored” by many users (with their names appearing on their posts), and users can always edit posts they are authors of. By default, users can edit every post on the site, but this permission can be switched off to give users access only to posts they are authors of.

- Full tracking and management of revisions to post content. Revisions are saved automatically by WordPress, but ALP adds additional capabilities to specify edit summaries to describe what you actually changed. These logs are listed under each post and page, and you may revert a post or page “back in time” to a previous version if you want, like Wikipedia pages.

- Cross-references. If you link to an old post, that old post shows that it has been linked to in a list under its content, letting you follow the chain of posts on a particular topic, and to easily work out if there has been a later update to a post’s subject since the post in question was published.

- Mathematical rendering in the browser, what-you-see-is-what-you-get, using KaTeX (which is far, far quicker than MathJax).

- Tables of contents and breadcrumb trails on pages. Sub-pages show a link to their parent, and page headings are used to build tables of contents like on Wikipedia pages.

- Clear separation between chronological and static content. Posts are used for writing about what you did in the lab. Pages, listed hierarchically in menus at the top of each page, are for writing down reference information that you will frequently look at again. Posts drop off the front page as new ones are added, but pages remain linked to from the menu at the top of the page.

The bad

Obviously I’m biased, but I should probably tell you about some of the bad stuff. Here goes:

- Single-person operation… for now. I am only one person, and while I enjoy developing web applications (most of the time), I have a day job and cannot fix bugs as quickly as a company you are paying. And, sometimes, I might just disagree that such a feature is really broken, or worth fixing! That being said, I do use my own system at work and bugs stick out to me like a sore thumb, and they usually distract me enough for me to fix them quickly. Just no guarantees!

- Only runs on modern browsers. The JavaScript-heavy Gutenberg editor used in WordPress needs an up-to-date browser. No running ALP on that old pile of crap at the back of the lab! (That being said, ALP works very well on mobile and tablet browsers!)

- Some plugins probably won’t work well alongside ALP. In particular, the modifications that ALP makes to the way post authorship works could break plugins that make similar modifications. However, if such plugins are useful to you, I am of course open to finding a way to get their features to work with ALP – either by making it compatible or merging/adapting the code.

- You can’t write full-blown rich text comments, or at least, not without knowing some HTML. ALP instead encourages users to make a new post if you have a lot to say in a response. The good thing about this approach is that if you link to the old post in your response, this will show up as a cross-reference underneath both posts, allowing you to easily follow progress across time. If you really want a rich text editor for comments, there are other plugins that can add this feature alongside ALP.

Others I’ve yet to review

I’ve discovered a bunch more options that I’ve yet to review, which you may be interested in testing (all of them are commercial):

Conclusion

Ultimately, what you choose to use for your lab is your business, and should be decided based on your users’ needs. It seems there aren’t so many choices available for online labbooks, and not many are still actively developed. You may wish to choose the safety of a professional company, or a well-tested solution that’s been around for a long time. But if you’re willing to take a punt on ALP, please dive in and let me know what you think! Future features will be influenced by user feedback!

Decided to choose ALP? Visit the ALP installation guide to get started! Decided not to choose ALP? If you have time, please let me know what you think is missing and I might try to add it in the future.

Thanks for reading!